Women have accused the singer of sexual abuse for decades. So why are they only being listened to now? Blame misogyny and racism – but also the potency of his musIC

“Yo, Pac!” You can almost feel the spittle as Gary Oldman launches into his soliloquy. It is 2012, and he is performing in a skit on Jimmy Kimmel’s US talkshow, reciting from R Kelly’s autobiography with the plummy majesty he later brought to the role of Churchill. “What up, baby?” he utters as the audience collapses in giggles. The joke is twofold: English people are so white! But also: R Kelly is so ridiculous!

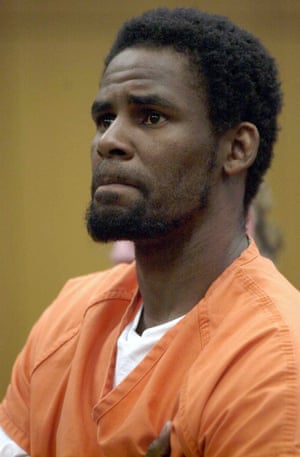

For years, Robert Kelly, now aged 52, was seen, as Kimmel put it that night, as “great and inexplicable”. He was one of the US’s most brilliant entertainers, beloved for his uproariously carnal R&B tracks and stratospheric ballads. But there was something that set him apart from his musical peers: a knowing ridiculousness, which would prompt him to cast himself in a 33-part television opera centering around a well-endowed dwarf, describe himself as a “sexasaurus”, and make Same Girl, his duet with Usher, so hammy it would inevitably be spoofed by Flight of the Conchords in a song called We’re Both in Love With a Sexy Lady. This sense of self-mockery gained him a new, white hipster audience – Pitchfork booked him to play its festival in 2013 – and also helped insulate him from criticism. Until now.

Timeline

What are the allegations against R Kelly?

It has been alleged for more than 20 years that Kelly has had abusive relationships with women. He wrote and produced Aaliyah’s debut album, then was reported to have married the R&B star illegally when she was 15. The album was titled – chillingly, in retrospect – Age Ain’t Nothin’ But a Number. In 1996, Tiffany Hawkins sued Kelly for “personal injuries and emotional distress” during a three-year relationship that began when she was 15 and he was 24. That suit, and three others since, were settled out of court. Kelly has only appeared before a judge once, in 2008, when he was accused of making child abuse images by filming sexual encounters, including one in which he urinated over an underage girl. A jury couldn’t identify the man or the girl in the video without doubt, and Kelly was acquitted.

Throughout all this, Kelly’s career flourished. Mark Anthony Neal, professor of black popular culture at Duke University, calls him “the most visible R&B star of the 1990s … we haven’t seen an R&B figure emerge post-R Kelly that has the kind of gravitas that he or Luther Vandross or Marvin Gaye had.” Kelly created radio hits that united races and generations, and wrote commercially blockbusting albums such as R, which in 1998 sold 216,000 copies in a single week in the US alone, and boasted duets with both Jay-Z and Celine Dion.

“He had a really good ear,” Neal says. “He couldn’t read or write music, but he was able to mimic these larger traditions: R&B, soul and gospel, adding a contemporary feel so that it felt urgent and vital. And he knew how to record raunch.”

Over the past two years, that success has been replaced with a flood of fresh accusations, including claims that he had sex with girls as young as 14 while running a cult-like harem. His ex-wife claimed that he choked her almost to death, part of a campaign of violence that made her suicidal. A social media campaign, #MuteRKelly, gained traction as the #MeToo movement caught fire.

Then, earlier this month, the documentary Surviving R Kelly aired on Lifetime TV in the US. In it, to devastating effect, numerous women accused the singer of sexual, physical and psychological abuse. After it screened, Kelly’s daughter Joann (who goes by the name Buku Abi) described him as a “monster”, adding: “I am well aware of who and what he is. I grew up in that house.” Activist group UltraViolet flew a banner over the offices of Kelly’s record label, demanding that it drop him. Following fresh appeals from prosecutors in Atlanta and Chicago, where Kelly has residences, three more women have come forward alleging abuse, along with two other families who say their daughters have gone to live with Kelly. Lady Gaga, Phoenix and Chance the Rapper expressed contrition for working with Kelly, while John Legend, Ne-Yo and Common condemned him.

What took them so long? Kelly denies all the accusations of abuse. His lawyer, Steven Greenberg, has threatened to sue Lifetime, and says that Kelly’s sexual relationships have all been “perfectly consensual”. Kelly’s denials include statements through his lawyers, plus a 19-minute song, I Admit, in which he sings that he has been “so falsely accused”, and that his accusers were financially motivated.

Complicating the accusations, one young woman has told police, who made a visit to one of Kelly’s homes, that she was living with Kelly consensually, and was “fine and did not want to be bothered with her parents”. Another told her parents – who said she appeared “brainwashed” – that “she’s in love, and [Kelly] is the one who cares for her.” A further police visit to a Kelly residence reported by TMZ this weeksaw two women repeatedly profess that they were safe and free to come and go. But they are outnumbered by women who do accuse Kelly of abuse. The sheer frequency – and pattern – of the accusations now means that even fans, and collaborators such Gaga, now believe the accusers.

What if Kelly’s alleged victims had been white? Jim DeRogatis, the Chicago-based journalist who has doggedly reported on Kelly for 17 years, has said that the saga has taught him: “Nobody matters less in society than young black women.” Or, as Mikki Kendall put it in Surviving R Kelly: “No one cared because we were black girls.”

“These black girls and women were not ‘ideal victims’,” says Treva Lindsey, a professor at Ohio State University whose research focuses on violence against black women. She has found “a particular kind of venom that is relatively normalised” towards them, which starts from the top: “Some of Trump’s most vicious attacks on individuals have come at the expense of black women, whether that’s [congresswoman] Maxine Waters or [journalist] April Ryan.”

The Kelly case itself, she says, is compounded by “a narrative around black women and girls being hypersexual. It’s such a fraught, racist history, specifically around sexual violence – black men being accused of raping white women being one of the primary factors in lynching, and black women being seen, legally, as unrapeable.” Lindsey believes that these ideas have become internalised by some African Americans: “‘Oh, those girls knew what they were doing.’ And that is part of why it becomes difficult to see a 14-year-old girl on a child abuse sex tape as wholly a victim.”

Chance the Rapper pointed to another reason why some have been slow to condemn R Kelly, saying: “We’re programmed to really be hypersensitive to black male oppression.” Lindsey adds: “There’s definitely black folks of all genders defending Kelly, who are fearful of what this means for this larger historical narrative of black men being inherently criminal and aggressive. In the context of a racist country, one black person’s actions become illustrative of the depravity of an entire community. Harvey Weinstein isn’t an indictment of white men. But R Kelly can be used by some as an indictment of black men.”

Although the rapper French Montana later said he supported the alleged victims, when asked about Kelly, he grumbled that “they don’t let nobody have their legendary moments” – a sentiment shared by another rapper, Waka Flocka Flame, who, in the wake of the Bill Cosby scandal, said: “Every time a famous minority make it, they throw salt in the game.” Kelly has tried to leverage this sentiment – a representative described the #MuteRKelly campaign as the “attempted public lynching of a black man who has made extraordinary contributions to our culture”.

It is precisely these contributions that are Kelly’s most potent weapon. Listening to him can feel like a struggle between two impulses – to condemn the abuser but adore the artist whose best work touches greatness. She’s Got That Vibe, his debut single from 1992, roared joyously out of the New Jack Swing scene and immediately established a core part of his appeal: the ability to sing lecherous lines (“The tight miniskirt you wear … I can’t help but stare”) with such earnestness that they almost appeared romantic. That earnestness was intensified on his biggest hit, I Believe I Can Fly, a ballad of self-determination so structurally perfect that the words didn’t feel outlandish or silly.

Kelly’s first US No 1, Bump N’ Grind, acknowledged the moral wrongness of his desires, but framed himself as helplessly in thrall to them – a cornily manipulative trick that the excellence of the songwriting makes seductive. Kelly had to present himself as defined and ruled by his sexuality, both to enhance his sex appeal and to absolve him of his problematic libido. Ignition (Remix) was one of the greatest pop songs of the 00s, its double entendres, car horns and atmosphere of three-drink tipsiness so potent that it became a global hit a mere four months after Kelly was indicted on 10 counts of child pornography.

Fans don’t want Kelly to be a paedophile or rapist because that would ruin the music. As Common said in the wake of the documentary: “Instead of trying to be like, ‘Let’s go and try to resolve this situation and free these young ladies and stop this thing that’s going on,’ we were just like, ‘Man, we rocking to the music’.” That effect has endured even now – streams of Kelly’s music have increased since Surviving R Kelly aired.

The love for Kelly’s songs such as these is intensified by their communal appeal: they are the soundtrack to joyful memories of dancefloors and karaoke. As Lindsey says: “His music signals so many moments for us, whether it’s weddings or graduations or your first kiss.” Neal agrees: “He knew how to make songs that a black community would find value in, in black social life,” he says. “Step in the Name of Love at weddings; I Believe I Can Fly – if you’re at a kindergarten graduation, you’re singing this song.”

Less successful singles were still touched with brilliance. One lyric on I’m a Flirt, “like a dog on the prowl when I’m walking through the mall”, is even more sinister when you consider, as Lindsey says: “Any of my black girlfriends from Chicago had an R Kelly story, and most of them involved a high school, or mall, these spaces where he clearly is finding vulnerable black girls.” But the line is – perhaps deliberately – given a spectacularly carefree, beautiful melody.

Listening now to songs such as I’m a Flirt, it feels as if Kelly was getting a kick out of hiding in plain sight. Many of his songs express a desire for control through marriage and impregnation in the starkest terms, such as Marry the Pussy and Pregnant. Songs such as It Seems Like You’re Ready are excruciating given what we know about Kelly’s penchant for underage girls.

Kelly also leveraged the very iconography of R&B. By brazenly embracing a cartoonishly horny image, from 1993’s I Like the Crotch On You to the faceless, naked women on the cover of his 2013 album Black Panties, he made the stories of “sex cults” seem like a joke. “This virility, sexually assertive to the point of aggressive, is a part of a particular R&B persona, and R Kelly is in tradition with that,” Lindsey says. Was Kelly really an abuser, audiences might wonder, or just participating in a tradition of playful lechery going back to 70s soulmen such as Marvin Gaye, Isaac Hayes and Teddy Pendergrass?

Then there are Kelly’s experiences as a victim of sexual assault: in his autobiography, he wrote that, growing up, he was repeatedly sexually abused by a family member. Was this the wellspring of his sexually aggressive lyrics, and his own alleged abusiveness as an adult?

Kelly’s case is complex: a knot of tensions around race, gender, sex and artistry that must be unravelled in order to ask hard questions about how it might have been allowed to flourish, and to bring justice to his alleged victims. “What would it mean to hold R Kelly accountable now?” Lindsey wonders aloud. It will surely take far more than removing his duets from Spotify, as Lady Gaga has done, in penance but also as a means of erasing the historical record. As Lindsey says: “There’s too much at stake for us not to figure it out.”

• Surviving R Kelly airs in the UK on 5 February, 10pm, on Crime and Investigation.

No comments:

Post a Comment